Replay: Assembling Together by Watchman Nee

Five years ago, I wrote a series of posts on Watchman Nee’s book Assembling Together. Overall, I found the book to be very informative, easy to read, and encouraging. I had already come to some of the same conclusions that Nee had come to, although we disagree in a few places as well. Below, I include the contents of the first post of the series “Assembling Together 1 – Joining the Church” along with links to the other posts. (By the way, the links will send you to my old blog at Blogger, but you will then be redirected back to the post on this site.) If you haven’t read this book yet, I would highly recommend it.

—————————-

Assembling Together 1 – Joining the Church

The first chapter of Watchman Nee’s book Assembling Together (chapter 14 of the Basic Lessons series) is called “Joining the Church”. This is a great chapter with which to begin to understand Nee’s ecclesiology.

The phrase “joining the church” is quite interesting. To Nee, this means something completely different to how I’ve seen this phrase used in contemporary churches in the United States. I think even Nee understands how this phrase is normally used. He says, “We do not like the phrase ‘joining the church,’ but use it temporarily to make the issue clear.” [1] So, what does Nee mean by “joining the church”? He first explains how believers immediately become part of God’s family upon salvation. He then specifies exactly what he means by “joining the church”:

A Christian therefore must join the church. Now this term, “joining the church,” is not a scriptural one. It is borrowed from the world. What we really mean is that no one can be a private Christian. He must be joined to all the children of God. For this reason, he needs to join the church. He cannot claim to be a believer all by himself. He is a Christian only by being subordinate to the others. [9]

Never once in the Bible do we find the phrase “join the church.” It cannot be found in Acts nor is it seen in the epistles. Why? Because no one can join the church… Rather, we are already in the church and therefore are joined to one another. [13]

When, by the mercy of God, a man is convicted of his sin and through the precious blood is redeemed and forgiven and receives new life, he is not only regenerated through resurrection life but is also put into the church by the power of God. It is God who has put him in; thus he already is in the church. [13]

Then why do we persuade you to join the church? We are only borrowing this term for the sake of convenience. You who have believed in the Lord are already in the church, but your brothers and sisters in the church may not know you. [14]

At this point, Nee remains close to Scripture. He is correct that “joining the church” is not a scriptural phrase, and is never commanded or exhorted in Scripture. Instead, we become part of the church when we are “born again” into the family of God. It is true that we may still need to seek out brothers and sisters with which to fellowship, but that is not the same as “joining the church”. Of course, the best place for a new believer to begin to find fellowship with other brothers and sisters is with the person or people who made the gospel available to him or her.

Next, Nee answers the question: which church should I join? Most believers today would probably disagree with his answer. First, Nee explains the rise of different churches and denominations based on time, area, human personalities, or a particular emphasis on one aspect of truth. He then says that all believers in a city form a city-church, and that is the church that a new believer should become part of. In fact, he argues that the only valid biblical definition for “church” (singular) is the city-wide church:

The Bible permits the church to be divided solely on the ground of locality… The smallest church takes a locality as its unity; so does the biggest church. Anything smaller than a locality may not be considered a church, nor can it be so recognized if it is bigger than a locality. [11]

This statement is problematic. Nee examines several passages to demonstrate that the singular “church” is used to represent all the believers in a given city. I do not have a problem with this analysis, except I think he left out a few key passages of Scripture. It is not true that the singular “church” is always used to represent all the believers in a city and that the singular “church” is only used to represent all the believers in a city. Here are a couple of passages that use the singular word for “church”, but may not represent all the believers in a city or the believers of only one city:

But Saul was ravaging the church, and entering house after house, he dragged off men and women and committed them to prison. (Acts 8:3 ESV)

Greet Prisca and Aquila, my fellow workers in Christ Jesus, who risked their necks for my life, to whom not only I give thanks but all the churches of the Gentiles give thanks as well. Greet also the church in their house. Greet my beloved Epaenetus, who was the first convert to Christ in Asia. (Romans 16:3-5 ESV)

I should also mention that in Acts 9:31, some manuscripts have the singular “church” (while others have the plural “churches”) for the believers in the regions of “Judea, Galilee, and Samaria”. There are also other passages that mention the “church” in someone’s house which may or may not be the entire church of a city.

So, I do agree with Nee that Scripture describes all the believers in a certain city as a “church” (singular). However, it appears that there may be smaller groups within that city-church that are nevertheless called “church” (singular). Similarly, in Acts 8:3, it appears that Saul is persecuting believers over a larger area than a city, but Luke still considers Paul to be persecuting the “church” (singular). The usage of the word “church” is more complicated that Nee makes it out to be.

There is one other point (and a major point, I think) with which I disagree with Nee. He claims that individuals are not the dwelling place of God; only the church is God’s habitation:

In the past God dwelt in a magnificent house, the temple of Solomon. Now He dwells in the church, for today the church is God’s habitation. We, the many, are joined together to be God’s habitation. As individuals, though, we are not so. It takes many of God’s children to be the house of God in the Spirit. [5]

Unfortunately, I do not think that Nee considered enough scriptural evidence. It is true that most of the references to the Spirit dwelling within beleivers occurs in the plural. But, of course, most of Scripture was written to communities of believers to be read to the entire community. It is also true that the Spirit dwells with the community; however, just as Solomon’s temple could not contain God, the community alone does not contain God’s Spirit. There are plenty of references to individual believers being filled with the Spirit of God (i.e. Acts 6:3, 9-10).

Besides these two points of disagreement, this is an excellent chapter. Nee encourages all believers to find other believers with which to fellowship. He especially exhorts new believers that they should not try to live in isolation.

I usually find the last paragraph of one of Nee’s chapters to be very helpful. Sometimes, even when I do not agree with Nee’s arguments, I agree completely with his conclusion in the last paragraph. I agree with much of this first chapter, and I also agree with his last paragraph:

You who are already in Christ should learn to seek the fellowship of the children of God. With this fellowship of the body you may serve God well. If you as young believers can see this light, you will move a step forward in your spiritual path. Thank God for his mercy. [15]

The next chapter in this book is called “Laying On of Hands.”

Review of Watchman Nee’s Assembling Together Series:

1: Chapter 1 – Joining the Church

2: Chapter 2 – Laying on of Hands

3: Chapter 3 – Assembling Together

4: Chapter 4 – Various Meetings

5: Chapters 5 & 6 – The Lord’s Day and Hymn Singing

6: Chapters 7 & 8 – Praise and The Breaking of Bread

Frame: The New Testament does not describe the early Christians as meeting for worship.

As I’m going through some of my research for my dissertation, I occasionally run across a quote that puzzles me. One of those is by the famous theologian and prolific writer John Frame. Frame often writes about worship, including the book Worship in Spirit and Truth which I include as part of the research for my dissertation. (By the way, for those who don’t know – and who care – the title of my dissertation is “Mutual Edification as the Purpose of the Assembled Church in the New Testament: A Study in Biblical Theology.”)

In his book, Frame comes to the same conclusion regarding the New Testament evidence as me. At one point, he writes:

Is the Christian meeting a “worship service”? Some have said no, on the ground that in the New Testament all of life is worship. It is true that the New Testament does not describe the early Christians as meeting for “worship.” Nor does the New Testament typically use the Old Testament language of sacrifice and priesthood to describe the Christian meeting as such. Much of the New Testament teaching about the meeting has a horizontal focus: the importance of showing love for one another in the meetings (1 Cor. 11–14), the importance of education (1 Cor. 14:26; Heb. 10:24–25). (pg 31)

Did you catch that? According to Frame, the authors of the New Testament do not use worship terminology to describe the times when believers gather together. They do not use the language of sacrifice or priesthood either, terminology often used in the Old Testament. Instead, again according to Frame, the authors of the New Testament – when writing about the assembled church – focused on “showing love for one another” and “the importance of edification.”

Yes, exactly. Again, that’s the same conclusion that I’ve reached through studying the New Testament.

Not only that, but Frame and I also agree when it comes to using “worship” terminology to refer to the gathering of the saints:

Traditionally, Christians have called it [the Christian meeting] ‘worship,’ having in mind a sense of the term that is analogous to its use in the temple setting. This use of the worship vocabulary is somewhat dangerous, for it may lead us to forget the vast differences that exist between Old Testament worship and the New Testament meeting. (pg 32)

Did you catch that also? Frame says that it’s dangerous for Christians to use “worship” terminology to refer to the times that we gather with our brothers and sisters in Christ. Why? Because it confuses “the vast differences that exist between Old Testament worship and the New Testament meeting.”

Yes, exactly. Again, that’s the same conclusion that I’ve reached through studying the New Testament.

So, what’s the problem? Well, while we agree about the New Testament evidence concerning the church meeting, Frame and I do not come to the same conclusion regarding our application of this evidence.

He writes:

Therefore, it is not wrong to describe the Christian meeting as, in one sense, a worship service. To say this, however, is not to say that there is a sharp distinction between what we do in the meeting and what we do outside of it. (pg 34)

So, Frame concludes, “Go ahead and call it a ‘worship service’ and describe what you do as worship – even though the New Testament authors did not refer to the gathering of the saints in worship terminology and even though using worship terminology is dangerous and even though there is no distinction between our worship when we are together and our worship when we are not together.”

Honestly, it just doesn’t make sense to me.

Who are the strong and who are the weak among the church?

Arthur at “The Voice of One Crying Out in Suburbia” recently wrote a short review of Dave Black’s new book Paul, Apostle of Weakness: Astheneia and Its Cognates in the Pauline Literature. Arthur’s review is called “Book Review: Paul, Apostle of Weakness.”

Last week, Arthur published another post called “The Strong Must Accept the Weak” in which he responds further to Dave Black’s new book. While his review is really good, I appreciated this post even more.

Arthur begins by reviewing his own history with the “strong” and the “weak”:

I have always gravitated toward traditions in Christianity that focus on “being right” and often those traditions made “being right” a lot more than just an honest attempt to live faithfully. Instead they all too often became a way to lord over the “less mature”, uninformed or just plain ignorant among the Body.

Arthus ends with some new thoughts after reading Black’s new book:

The church is not set up to be a place where the strong dominate the weak but where the strong love the weak.We tend to naturally gravitate to a hierarchy where we place the strongest at the top and the weakest at the bottom. The strong are recognized by title and prestige. There is of course nothing wrong with recognizing the more mature among us but they should be noted for their service and exemplary lives, not for dominating and demanding.

The church is only as strong as it treats the weakest among us. If we see the weak as people to be ostracized and avoided lest they infect us or as fools to be corrected by our superior knowledge, perhaps we are not quite as strong as we think we are.

As I read through Arthur’s post and as I thought about this topic (i.e., Paul’s use of the term “weak” – astheneia), I realized something.

There are times when Paul counts himself among the “strong”:

We who are strong have an obligation to bear with the failings of the weak, and not to please ourselves. (Romans 15:1 ESV)

And there are times when Paul counts himself among the “weak”:

If I must boast, I will boast of the things that show my weakness. (2 Corinthians 11:30 ESV)

So, is Paul “strong” or “weak”?

Typically, today, when people talk about the “strong” and the “weak” among the church, they point to some as being the “strong” and others as being the “weak.” The strong are always strong, and the weak are always weak. (By the way, I’m not suggested that either Arthur or Dave Black are saying this. I’m simply relating the way I’ve typically heard these terms used.)

However, it seems that Paul thought that he could be strong at times and weak at other times. And, I think this is the right way to think about this. I can be strong at times, and I can be weak at times. Sometimes, you are strong; at other times, you are weak. This is true of any followers of Jesus Christ – male or female, young or old, mature or immature.

And, it also seems that the “weak” rarely recognize their weakness, but often they see their weakness as a strength.

If we recognize this in ourselves and others, we would accept that we might be the “weak” and our brother/sister might be the “strong” in any particular situation. We would treat our brothers and sisters in Christ with more respect and honor, even when we disagree with them.

I think this would greatly improve our ability to relate to one another, to disciple one another, and to be discipled by one another.

What do you think? Would it be beneficial to treat someone with whom we disagree as “strong” instead of “weak”? How would it benefit our relationships and ability to disciple one another if we recognized that we may actually be the “weak” party?

Replay: Does acceptance of others make our beliefs illegitimate?

Three year ago, I wrote a post called “Does acceptance make our beliefs illegitimate?” Among many Christians today (and for the last several hundred to two thousand years) there is a huge problem when it comes to unity. The problem is that we assume that accepting someone as a brother or sister in Christ means that we must set aside all of our beliefs and convictions. It means we must agree with everything that they other person believes. (Well, to be honest, most separate “doctrines” into different groups with each group allowing different levels of agreement.) I think this practice is a huge slap in the face to our unity in Christ.

————————-

Does acceptance make our beliefs illegitimate?

Recently, when reading about the Jewish influence on the early church, I came across this interesting paragraph:

For the Jewish Christians in Jerusalem, however, the issue [of circumcision of Gentiles] was not so clear. The inferences were obvious to them; the ramifications were potentially damaging to the Jewish traditions. That God had poured out his Spirit on the Gentiles was amazing in its own right; but the subsequent inference that the Jewish believers would be required to accept (and even have table-fellowship) with the Gentile Christians without the latter having to undergo circumcision or to observe the law brought into question the legitimacy of the Torah. (Brad Blue, “The Influence of Jewish Worship on Luke’s Presentation of the Early Church,” in Witness to the Gospel: The Theology of Acts (ed. I. Howard Marshall and David Peterson; Grand Rapids: Eerdman’s, 1998) , p. 492)

An amazing thing happened in those early years after Pentecost (as recorded by Luke in Acts). God’s Spirit began to indwell people… and not just Jews, but Gentiles as well.

Before, Jews would only interact with Gentiles when required to (for instance, the Roman army or government officials) or when the Gentiles agreed to be circumcised and keep the law. In other words, if it were up to the Jews, they would only spend time with people who were like them and who believed like them.

But, now, the Holy Spirit was indwelling uncircumcised, law-breaking Gentiles, and the ramifications of this indwelling was about to turn the Jewish-Christian’s view of the world upside down. They knew that they were required (by their common relationship to God and by the common indwelling of the Spirit) to not only spend time with these new Gentile Christians, but to treat them as brothers and sisters!

Outrageous! And, many of those Jewish Christians refused, fought, argued, kicked-and-screamed against this type of behavior. They knew exactly what this kind of acceptance meant. If the Jewish Christians accepted the Gentile Christians as brothers and sisters, then the Jewish Christians would have to admit that neither circumcision nor keeping the law were necessary for God’s acceptance.

Thousands of years of traditions and belief were about to be thrown out the window because God was accepting, saving, and indwelling Gentiles.

Now… today… what are we going to do when we recognize that God is accepting, saving, and indwelling people from different traditions and with different beliefs? Are we going to accept them? Or, are we going to refuse, fight, argue, kick-and-scream against the work that God is doing?

Can we admit that God can accept, save, and indwell people who do not have the same traditions, practices, and beliefs as us? Are we willing to admit that our traditions, practices, and beliefs are not necessary for God to accept, save, and indwell someone?

2012 Book of the Year

Each year since I started blogging, I’ve chosen a “book of the year” from one of the books that I’d read for the first time during that year.

This year, I’m doing something a little different. I’m still choosing a “book of the year,” but I’m not choosing a book that I read for the first time during 2012. Instead, I’m choosing a book that I re-read during 2012. (I first read this book before I started my blog, so I’ve never chosen it as “book of the year” before…)

So, I’m choosing Paul’s Idea of Community: The Early House Churces in Their Cultural Setting by Robert Banks as my “book of the year” of 2012.

Like I said, I re-read this book in October 2012, and I wrote a few posts reflecting on a few of the chapters. Here are those posts:

- “For Paul, freedom means independence, dependence, and interdependence“

- “The ekklesia that actually gathers in a location“

- “The ekklesia as a heavenly reality“

- “The Body Metaphor in Paul: Familiar and yet unique“

- “A structure that emerges naturally based on the people involved“

I read this book at a time when I was trying to decide whether or not to continue my academic pursuits. This book helped me see that my views of the church could be expressed in a scholarly way. (Interestingly, the book was recommended by a professor who does not share my views of the church…)

So, if you haven’t read this book, I would definitely recommend it!

Finding Church – a new book with 36 authors (including me)

Last spring, my friend Jeremy from “Till He Comes” asked if I’d be interested in writing a chapter for a new book that he was putting together. He was asking people to write on one of four topics: changing churches, leaving church, reforming the church, and returning to church. I decided to take part in the project by writing a chapter on one of the topics.

I later wrote a series of blog posts about the project, with an introduction and one post for each topic: changing churches, leaving church, reforming the church, and returning to church. If you haven’t read those posts, I hope you will, because I think they help explain my understanding of church, and how that understanding has changed over the last few years.

In all, Jeremy gathered 36 different authors to write for this project. In the end, he condensed his 4 topics into 3: leaving church, switching church, and reforming church. He told us about all 36 authors in a post called “All the Finding Church Authors.” (Click each name to learn more about that particular author.)

(By the way, my chapter is in the section “reforming the church.”)

The book is now available. You can find out more from Civitas Press (the publisher), and you can even buy it on Amazon in paperback or for your Kindle device.

Here’s the publisher’s blurb about the book:

What happens when people begin to question church?

Millions of people are “leaving church” each year as they begin to question the deeper meanings and structures of gathering together. They’re asking a fundamental question of, “What does it mean to participate in church and what would happen if we did something different?”

They are not abandoning God, ignoring Scripture, or giving up on Jesus. While a few do leave for such reasons, the vast majority report that they leave church to better follow Jesus, obey God, and live out their faith in meaningful and relational ways. They stop attending church to pursue something more intimate and personal.

Finding Church explores these stories of people leaving, switching, and even reforming their basic understanding of church. It will open your eyes to a growing trend in culture for people to take responsibility for their faith.

I haven’t received my author’s copy of the book yet. But, when I do, I hope to read the other chapters and write a review. If you read the book, please let me know what you think (both about my chapter and the other chapters).

A structure that emerges naturally based on the people involved

As I mentioned a few weeks ago, I’ve been re-reading one of my favorite academic books on the church: Paul’s Idea of Community by Robert Banks (Peabody: Hendrickson, 2004). I recently came across one of my favorite sections of this book, and I realized that I have not written about this particular topic in a while.

You see, when it comes to the church – and especially to gathering together with other believers – structure often takes center stage in any discussion. We tend to focus on questions like these: What should happen when we gather together? Who should speak when we gather? What order should things happen in? What if something goes wrong?

These are all questions related to structure. And, I think that Banks’ approach would help us deal with these kinds of questions any many others.

He writes:

So then, provided certain basic principles of teh Spirit’s operations are kept in view: balance, intelligibility, evaluation, orderliness, and loving exercise, Paul sees no need to lay down any fixed rules for the community’s proceedings. There is no one order proper for its meetings; any order is proper so long as these criteria are observed. Paul therefore has no interest in constructing a fixed liturgy. This would restrict the freedom of God’s communications. Each gathering of the community will have a structure, but it will emerge naturally from the particular combination of the gifts exercised. (page 105)

Interestingly, I’ve found that today’s concerns regarding gathering with believers are rarely the same as Paul’s concerns. Oh, we care about “orderliness,” but we define “orderly” in a different way than what Paul described when he used that term.

And, “any order is proper”? That seems so strange to us. No fixed liturgy? (Yes, some do not use the term “liturgy” but prefer the term “order of service.”) That seems strange to us to.

No one wants to “restrict the freedom of God’s communications.” But, when we realize that God chooses to speak to his children through each other, we recognize that we are limiting God’s communication when we limit who is allowed to speak.

In other words, like I said before, our concerns are much different from Paul’s concerns. By setting aside Paul’s concerns, we may create a nice, ordered (not orderly, but ordered) meeting, but we miss much of what God is communicating to us.

So, what kind of structure do we find in the church gatherings in Scripture. Well, Banks ends his statement above with this: “[B]ut [the structure] will emerge naturally from the particular combination of the gifts exercised.” And, the gifts are exercised by God people. The structure, then, emerges naturally through the people who are gathered together as God directs them to serve one another while they are gathered together.

This can’t be planned. It can’t be orchestrated. It can’t be predicted. It can’t be charted.

Like Banks says, it emerges naturally. Or, perhaps it would be better to say, it emerges supernaturally.

Replay: Gospel, Community, and Sermons

Two and a half years ago, I wrote a post called “More Gospel, Community, and Sermons.” The post was actually a follow-up to another one called “Another Word About the Sermon.” Both posts were inspired by a conversation that I had with a friend about a certain book and about sermons. The point in this post is to encouraging teaching through life-example along with teaching through words.

—————————

More Gospel, Community, and Sermons

Last week, I quoted Tim Chester and Steve Timmis’ book Total Church: A Radical Reshaping around Gospel and Community (see my post “Another Word About the Sermon“). When I found that quote, I also found that I had marked these two passages from the same book:

James says, “Do not merely listen to the word, and so deceive yourselves. Do what it says” (James 1:22). We must not only listen to the word – we must put it into practice. Churches are full of people who love listening to sermons. But sermons count for nothing in God’s sight. We rate churches by whether they have good teaching or not. But James says great teaching counts for nothing. What counts is the practice of the word. What counts is teaching that leads to changed lives. We must never make good teaching an end in itself. Our aim must be good learning and good practice. And that is a radically different way of evaluating how word-centered we are. (pg. 116)

Let us make a bold statement: truth cannot be taught effectively outside of close relationships. The reason is that truth is not primarily formal; it is dynamic. The truth of the gospel becomes compelling as we see it transforming lives in the rub of daily, messy relationships. (pg. 188)

Think about it this way: our teaching by mouth (whether lecture, dialogue, discussion, or other method) is ineffective if it is not accompanied by teaching by example and practice. I can teach by mouth, “Love one another,” and I can even get everyone to memorize the command, “Love one another.” But, neither of these indicate that I have truly taught “Love one another” or that anyone has truly learned “Love one another.”

My words “Love one another” must be accompanied by real actions demonstrating “Love one another”. Note that when I said “teaching by example and practice” above, I did NOT mean giving verbal illustrations. Verbal illustrations are simply another way to teaching by mouth. Instead, I must teach people with my life. So, it is imperative that my teaching be done in the context of real, life-sharing relationships.

I’ve offered several examples from Paul in the past, particularly from 1 Thessalonians 2:8-10 and 2 Timothy 3:10-11. However, there is also a very powerful example from Jesus in the Gospel of John:

Jesus, knowing that the Father had given all things into his hands, and that he had come from God and was going back to God, rose from supper. He laid aside his outer garments, and taking a towel, tied it around his waist. Then he poured water into a basin and began to wash the disciples’ feet and to wipe them with the towel that was wrapped around him… When he had washed their feet and put on his outer garments and resumed his place, he said to them, “Do you understand what I have done to you? You call me Teacher and Lord, and you are right, for so I am. If I then, your Lord and Teacher, have washed your feet, you also ought to wash one another’s feet. For I have given you an example, that you also should do just as I have done to you. (John 13:3-5, 12-15 ESV)

Jesus taught with his words and with his actions. We need to do likewise.

Remember that Chester and Timmis said, “Our aim must be good learning and good practice. And that is a radically different way of evaluating how word-centered we are.” How would we measure “good learning and good practice”?

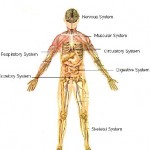

The Body Metaphor in Paul: Familiar and yet unique

Like I’ve mentioned in my last few posts, I’ve been re-reading one of my favorite academic books on the church: Paul’s Idea of Community by Robert Banks (Peabody: Hendrickson, 2004). So far, I’ve discussed Banks’ examination of Paul’s idea of salvation as freedom (“For Paul, freedom means independence, dependence, and interdependence“), Paul’s use the term ekklesia to refer to groups of believers who actually gather together (“The ekklesia that actually gathers in a location“), and Paul’s use of the term ekklesia to refer to our heavenly reality of being raised and seated together with God in Christ (“The ekklesia as a heavenly reality“). (By the way, this will be my last post on this book for now. Although, this topic has inspired me to study the “body” metaphor in Paul’s writings. That study will probably result in a series of blog posts, perhaps to be published next week.)

In the next couple of chapters, Banks looks at Paul’s use of family language and his use of the “body” metaphor. For each of those, he found some vague parallels in other religions and philosophical societies. However, in each case, Paul’s use of the language and metaphors was different from what he found in other writings and communities.

For example, consider this summary about Paul’s use of the “body” metaphor in relation to other religions and societies:

How original is Paul’s use of the “body” metaphor? It has no exact parallels in Jewish literature. Although the notion of “corporate personality” is present in the Hebrew Bible, it was the Greek translation of the OT that introduced the term “body” into Jewish thought for the first time (e.g., Lev 14:9; Prov 11:17). Yet neither here nor in the literature of the intertestimental period was the term used in any metaphorical way…

Gnostic thought recognizes the idea of the saved community as the body of the heavenly redeemer but only in writings that are later than the NT. In any case, Paul’s initial use of the metaphor, in which the community is represented by the whole body and the emphasis is upon the interdependence of its members, has no parallel in Gnostic sources.

In Stoic literature prior to the NT, we do find the cosmos (including humanity) depicted as the body of the divine world-soul and society as a body in which each member has a different part to play. But Paul refuses to portray the universe as Christ’s body and rejects any idea of a member’s wider society having priority over the Christian community. Individual and community are equally objects of his concern; neither is given priority over the other…

While none of these usages yields an exact parallel to [Paul’s] ideas, they do indicate the extent to which the metaphor was “in the air” in Hellenistic circles. While the term “body” did not originate with him, Paul was apparently the first to apply it to a community within the larger community of society and to the personal responsibilities of people for one another rather than their civic duties. We see again how a quite “secular” term is used by Paul to illuminate what Christian community is all about. (pp 65-66)

There is a great lesson for us in Banks’ comments. As we read ancient documents (and modern writings for that matter), we often find similar terms, phrases, metaphors, and illustrations. But, the fact that a person or community uses similar language does not mean that it is used in the same way. We must look at each usage in context to determine what the author intends to communicate.

While this is true in comparing Paul’s writings (and other NT writings) to nonChristian writings, we also must compare different usages of terms and phrases within Paul’s writings. Why? Because he could use the same terms, phrases, and especially the same metaphors for different reasons.

(By the way, this last statement is the reason that I’m planning to study Paul’s use of the “body” metaphor in each of his usages.)

The ekklesia as a heavenly reality

In my previous post (“The ekklesia that actually gathers in a location“), I explained that I’ve been re-reading one of my favorite academic books on the church: Paul’s Idea of Community by Robert Banks (Peabody: Hendrickson, 2004). Banks says that in Paul’s earlier letters (1-2 Thessalonians, Galatians, 1-2 Corinthians, and Romans), he only uses the term ekklesia to refer to groups of believers that actually gather together at some point.

However, when he turns to the letters to the Colossians and Ephesians, Banks finds an extension to Paul’s use of the term ekklesia. While he continues to use the term to refer to believers who actually gather together, he also uses the term to refer to “a heavenly reality.”

Banks says this concept is not new and that it can in fact be found in the earlier letters. However, it is not until the letters to the Colossians and Ephesians that Paul uses the term ekklesia to refer to this “heavenly reality.” But, Banks says it would be incorrect to equate this “heavenly reality” with the concepts of a “universal church” or an “invisible church.”

So in Colossians we are introduced to the idea of a nonlocal church of whom Christ is the head (Col 1:18,24). This notion is generally misinterpreted as a reference to the “universal church” that is scattered throughout the world. It is not an earthly phenomenon that is being talked about here, but a supernatural one. The whole passage in which the expression [ekklesia] occurs focuses on the victorious Christ and his kingdom of light that believers have now entered (1:9-2:7)…

If any hesitation remains about the possibility of understanding ekklesia as a heavenly assembly in Colossians, it is dispelled by the language used in Ephesians. There it is explicitly said that God “made us alive together with Christ… and raised us up with him, and made us sit with him in the heavenly places in Christ Jesus” (Eph 2:5-6 RSV)… Here again we see church taking place in heaven and Christians participating in it, even as they go about the ordinary tasks of life. Metaphorically speaking they are gathered around Christ, that is, they are enjoying fellowship with him. (pp 40-41)

So, according to Banks, Paul now has used the term ekklesia to refer to two different gatherings: 1) actual physical gatherings at certain times and certain places on earth and 2) heavenly gatherings in which all of God’s children are already raised and seated with God in Christ. The physical ekklesia, then, is a representation of the heavenly reality. And the fact that all believers were already gathered as a heavenly reality (not any kind of organization or structure) is the basis of expanding fellowship and relationships on earth:

These scattered Christian groups [churches] expressed their unity not by fashioning a corporate organization through which they could be federated with one another, but rather in a range of organized personal contacts between people who regarded themselves as members of the same Christian family.

So, Paul’s use of ekklesia as a “heavenly reality” should not be misunderstood as some type of umbrella organization. It is similar to the understanding that we are all part of the real family of God in Christ even though we may never meet each other in this physical reality on earth.

So, what do you think of Banks’ description of Paul’s reference to the ekklesia as a “heavenly reality.”?